Many people want to help those in need. But sometimes, the way we help can hurt more than it helps—especially if it takes away a person’s sense of dignity or worth. A short story or memory can help us think more clearly about this problem. Here is a reflection and answer on what real charity looks like.

Q: I knew a priest in a small parish. Poor people would come to him asking for food. He would hand them a broom and ask them to sweep the church parking lot while he prepared them something to eat. If they didn’t try hard, they got no food. I also noticed that mulberries are a kind of fruit that you can only eat if you pick them yourself, because they are so fragile. You never see them in the grocery store. And I think the Bible says farmers should not go back to collect parts of the harvest they missed, so poor people could gather it. I also remember President Reagan told a story about a little girl who wanted to help the poor. He said, “Go pick some fruit, sell it, and give the money to someone who needs it.” But the girl asked, “Why can’t the poor person just pick the fruit himself?”

A: You are touching on an old and important question: how can we help people in need in a way that also respects their dignity?

Let’s look at each of the stories you shared:

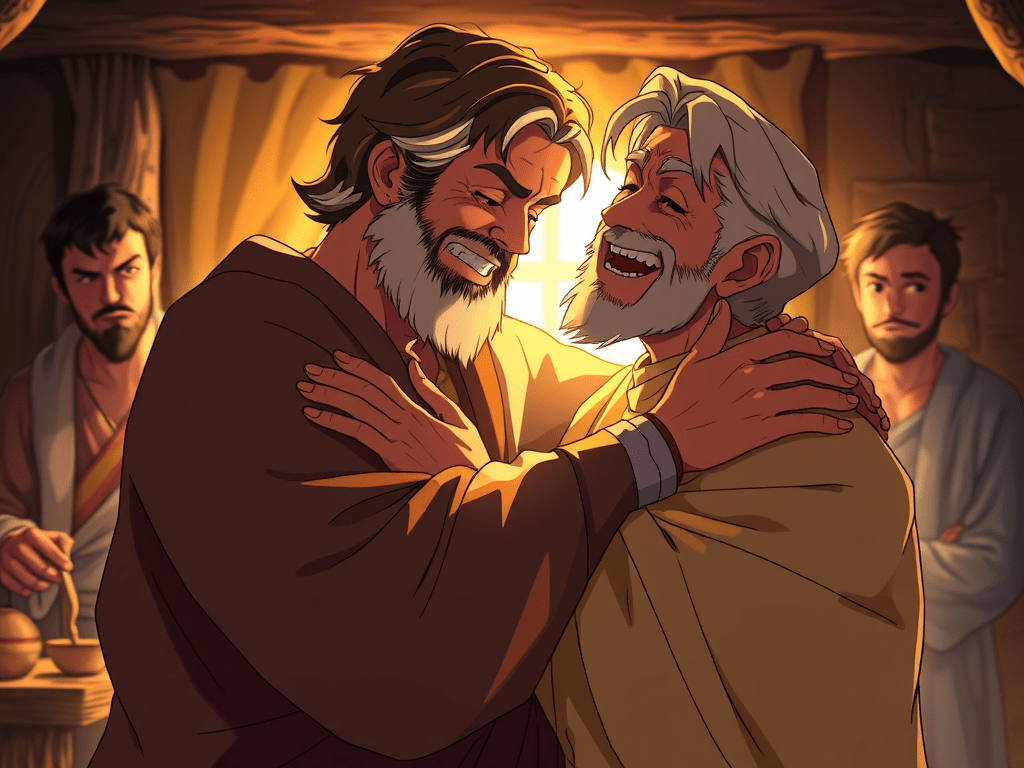

The priest with the broom: He gave food, but only after asking for a little work. This shows a deep kind of wisdom. He didn’t just feed the person—he helped them feel useful. He gave them a way to take part in the life of the church. That kind of charity is not just about giving things away. It is about helping people stand on their own feet. Saint Paul wrote something similar: “If anyone is not willing to work, let him not eat” (2 Thessalonians 3:10).

The mulberries: These fruits are a great picture of how effort and reward often go together. They are too soft and delicate to sell in stores. If you want to enjoy them, you have to go out and pick them yourself. Nature sometimes works this way—some of the sweetest things can only be reached through hard work.

The Bible and gleaning: In the Old Testament, farmers were told not to harvest every last bit of their crops. They had to leave the edges and anything they dropped for the poor to gather. But the poor still had to go out and pick it up. This wasn’t just a free gift—it was an opportunity to work and eat. It kept both justice and dignity.

Reagan’s story: The little girl’s question—“Why can’t the poor pick the fruit themselves?”—might seem harsh, but it shows a real problem. Sometimes, people who want to help forget that the best kind of help doesn’t do everything for someone. It gives them a way to help themselves.

So what do all these examples show?

The best kind of charity is not just about making people comfortable. It’s about giving them a way to grow, to work, and to feel human. When we give without asking anything in return, we might take away a person’s chance to feel useful and strong.

Real love doesn’t just give. It invites the other person to join in, even if it’s something small—like sweeping a parking lot or picking fruit. That kind of charity is full of truth. And it helps people become whole again.

Conclusion:

Real charity is not soft or weak. It is strong and wise. It gives people what they need, but also calls them to take part in their own healing. When we help others, we must remember: giving is good—but giving in a way that respects a person’s dignity is even better. That is love with truth.

Q&A with ChatGPT