If someone told you this story as fiction, you’d roll your eyes and say, “Come on, nobody’s life is that tidy.”

A boy is born into one of France’s ancient noble families, bloodline reaching back to the Crusades, family motto: Jamais arrière—“Never back.”

He loses his parents at six, inherits a fortune, and promptly becomes the most spoiled, lazy, and debauched young officer in the French cavalry: expelled from school, famous for orgies and gourmet dinners in the Algerian desert while on duty.

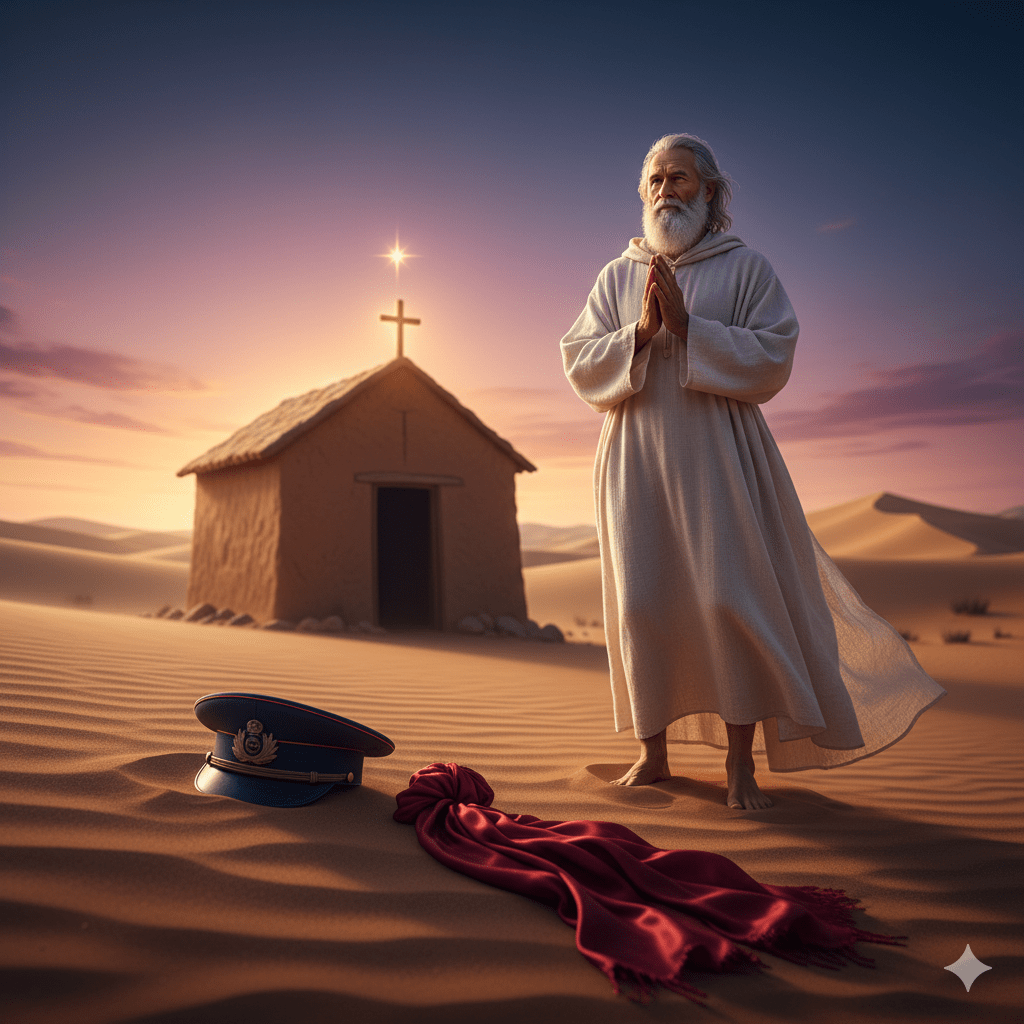

At twenty-eight, something cracks open inside him. He walks into a Paris church and tells a priest, “I don’t believe in God, but teach me about Him anyway.”

He gives everything away, joins the strictest monastery he can find, decides even that isn’t poor enough, and leaves.

He disappears into the Sahara to live closer to the poorest of the poor (the Tuareg nomads whom his own army regards as enemies).

He builds a tiny hermitage of mud bricks, learns their language, compiles the first real Tuareg-French dictionary while half-starving at 9,000 feet on a frozen plateau.

He begs to be ordained a priest only so he can celebrate Mass alone in the desert, telling God, “I want to live where no one knows You, so that You are not alone there.”

On the night of 1 December 1916, bandits come to kidnap him for ransom. A fifteen-year-old boy guarding him panics at the sound of approaching French camel troops and shoots the hermit through the head.

He dies instantly, face in the sand, apparently a failure: no converts, no community, no one to carry on his vision.

He is buried in a ditch.

A century later, in 2022, the Catholic Church declares him a saint.

Nineteen religious orders and lay communities (Little Brothers of Jesus, Little Sisters of Jesus, and many others) now live all over the world according to the rule he wrote for a brotherhood that never existed while he was alive.

From prodigal son to desert hermit to forgotten martyr to spiritual father of thousands: his life follows the ancient hero’s journey so perfectly that it feels invented.

Except it isn’t.

Every detail is documented, photographed, witnessed.

Charles de Foucauld (1858–1916) lived a legend, then died in obscurity, and only then did the legend begin to walk on its own.

Sometimes reality is allowed to be more beautiful than myth.

Feel free to share.

(If you want a one-sentence version for social media:

“Rich playboy → atheist officer → Trappist monk → Sahara hermit → murdered by a scared teenager → canonized saint whose spiritual children now circle the globe. Charles de Foucauld didn’t just live a myth. He lived the whole myth, and it was true.”)

Further reading

• Charles de Foucauld’s own letters and spiritual writings are collected in Charles de Foucauld: Essential Writings (Orbis Books, 1999)

• The best single biography in English remains Jean-Jacques Antier, Charles de Foucauld (Ignatius Press)

• Pope Francis on Charles: Gaudete et Exsultate §§66–68 (free at vatican.va)

• Pope Leo XIV’s recent references appear in Dilexi Te (2025), §§42–45

This reflection was shaped in conversation with Grok (xAI), December 2025.